designing identity

The story of a DNA test, an exploration of the ramifications of consumer genetic testing, and a study of how ancestry.com designed culture commodification

anthropology + design

Graduate Seminar @ The New School | Fall 2020 | Prof. Shannon Matternby alexa mauzy-lewis

Original Header Image by Janna Stam on Unsplash* disclaimer *

Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals. I have tried to recreate events, locales and conversations from my memories of them

“it’s not just a matter of what you claim, but it’s a matter of who claims you.”

quote: Kim Tallbear | image: the author and her half-sister, rancho peñasquitos, circa early 2000’s“You know as soon as my Dad dies, I’ll stop having a reason to stay sober like what's the point?” Tasha’s voice ricocheted out of my phone and around the four walls of my apartment. She took very few breaths in between her ramblings, pausing only for a drag of a cigarette.

“Do you mind if I smoke,” she had asked.

“No, I’m not even there,” I laughed nervously.

“Oh, right” she coughed back.

I could hear the distinct breath, a slow inhale, the light crackling, nearly smelling her in my living room. The same sounds and smells that trailed my mother. Sitting on my flimsily tiled floor, leaning against the broken futon, I tapped my fingernails against the coffee table. I glanced at the clock, counting the seconds of our call. She had been talking at me for almost two hours now, attempting to summarize a lifetime. I hadn’t said much, just a few obligatory “ahs” and “oh no’s.”

“So, what is your mom like, my sister, what is she like?” Tasha’s voice, raspy yet somehow still girlish, oozed excitement. I didn’t know what to say.

I looked up at my cat, his entire face smushed against the window, tail erect and twitching, watching a single sparrow idle around the patio. To his left was a photo of my dad, his arm slung around my shoulder at my high school graduation, both of us beaming under two pairs of the same nose. I thought about grabbing my phone to take a picture of the sparrow, she looked like she was collecting things for a nest. I had recently taken to watching birds. Sparrows often remain faithful to their mating partners for life, nesting in small flocks. I wondered where this particular sparrow’s clan was.

I realized I let too many moments pass without responding to Tasha’s question. But I wasn’t about to spill my heart out to this woman I didn’t know.

“I don’t know if her story is mine to tell,” I sighed.

***

For the low price of $99, Ancestry.com promises you “insights from your DNA, whether it’s your ethnicity or your family’s health.” Claiming to have tested over 16 million people, their revenue was over $1 billion in 2017. A similar company, 23andMe has more than 10 million.

With their “state-of-the-art” headquarters nesting in Lehi, Utah, Ancestry® is the largest for-profit genealogy company in the world. It started in the 80’s as a publishing company selling genealogy reference books. They then launched an online service for organizing family trees, and eventually entered the DNA testing arena. Over the past decade, Ancestry-esque services have mushroomed. Beyond filling out family trees, DNA was, for a moment, looked to as the future of medicine. The time between 2017 and 2019 saw the most rapid growth for companies of this vein. When it launched in 2008, a similar company 23andMe boasted “Genetics just got personal.” Consumers could now decode the health risks written into their genetic makeup, seek personalized medicine, and maybe just find themselves along the way, by unlocking the rich histories of their bloodlines.

This growth swiftly peaked and came to a rushed halt. DNA testing turned out to provide little medical ingenuity and subscribers were left with not much more than a glorified social media network for their genes. This year, 23AndMe sold its rights to foreign pharmaceutical company. Weeks later, the CEO enacted massive layoffs, pointing to privacy concerns for the reason DNA consumer tests plummeted. The DNA business at large took a tremendous hit. DNA start-ups offering “direct-to-consumer” genetic tests were scrutinized for what they could do with this incredibly valuable data. The uncomfortable reality of the power of DNA collecting came full force into public consciousness with the arrest of the Golden State Killer. Using the service GEDmatch, law enforcement was able to track him down through scarce DNA traces to his fourth cousins. Public DNA databases could be used to find you without you ever needing to submit your own test. Consumers began to question: how else can our DNA be sold and bought and used against us? Could tech companies market to us based on genetic tendencies? Could DNA be sold to third parties and influence insurance premiums and bank loans?

In the decline of users and skepticism towards the inconclusive health diagnostics, Ancestry.com has leaned back into its origins as a “family history” business, campaigning around this past International Women’s Day and encouraging consumers to “discover how your family story was shaped by defining moments in suffrage history.”

For the millions of us who already rushed to turn our genetic makeover over to Silicon Valley in the name of self-discovery, more was revealed than a genetic proneness to diabetes, half percent French lineages, and, if you were lucky, trace blood-ties to a suffragette.

There are other things that lurk in our DNA. Family secrets taken to graves, scorned lovers, lost children. The answers that were promised by DNA matching produced more murky questions about the nature of identity and family. You could use your body to try to predict its own failures, find out where it came from, and where it was going. But then, what do you do with this information? And what do you do with the people revealed to you along the way?

These services have led to larger ethical concerns and unintended consequences of a genealogy database, and warp our understanding of ourselves, our community, and our family.

How are these DNA testing services designed to misinterpret culture, commodify identity, and profit off an obsession with understanding where we come from?

***

“what a fuss for a name: famous or not, it's only a ribbon tied around a sack randomly filled with blood, flesh, words, shit, and petty thoughts.”

quote: Elena Ferrante, The Story of the Lost Child | image: deconstructed preview of the author's ancestry.com family treeIn 2016, my grandmother paid for an Ancestry.com test to arrive at my apartment in Brooklyn, unannounced. Organizing the family tree was to be her hobby this year, participation was mandatory. I rolled my eyes opening the box, thinking of her quest to confirm her icky obsession with a miniscule tie to the Sioux tribe. Grandma Catherine had adopted my mother, but I knew she already had the ethnic background of her daughter’s birth parents in hand.

There was a lot I didn’t know about my mother, but nothing a DNA test could tell me. My parents weren’t married when my mom found out she was pregnant. They worked together when they were in their mid-twenties. Almost a decade later, they met again by chance. Their connection was brief. By the time she told him, my dad was already dating and soon to be engaged to my now stepmother. They all resolved to share me until I was seven. During this time, her prescribed back pain medication catalyzed into an opioid addiction, exacerbating the tendencies of her Bipolar disorder, yet to be diagnosed. I don’t remember much about living with my mom. There are a few bright moments I can recall, riding razor scooters together to school and eating T.V. dinners in front of cartoons. There are also the skipped meals, forgotten school pickups, murky half-memories of nights left alone with her boyfriend when she worked late. There was the day she picked me up from school without shoes on. That same night she broke her arm, inexplicably slamming it through a glass window in her bedroom. Hearing the shatter, the upstairs neighbors in our apartment complex called the cops. The officer on duty was my uncle. He found me hiding under my bed. My dad picked me up from the police station at 4 a.m.

Following the overdose and a bitter custody battle, I permanently moved in with my dad and my stepmother, Dana, now their full-time child. After a year of often-missed court-allowed supervised visitations, I didn’t see my mother again until I was eighteen.

My father did his best to give me a pretty normal life. I learned how to be without her. We lived in a house in the suburbs of Southern California. I played on the softball team and joined the high school newspaper staff. I had an after-school job tutoring and finger-painting with elementary school children. Dana raised me and my two little half-sisters, I adored them fiercely. We all fought with each other constantly, like sisters, daughters, and mothers will do.

Weeks before eighteenth birthday, three months before I was set to move across the country for college, my grandmother picked me up to go to lunch together. Without leaving my father’s driveway, she wordlessly handed me a letter written on five pages of torn yellow notepad paper. My mom was living in a halfway house in La Mesa, 45 mins away.

Four years later, sitting in my Flatbush apartment filled with Craigslist roommates and finishing my last year of undergrad, I sat on a wobbly kitchen table stool with a white box in my hands, a simple logo Ancestry DNA, promising me this is “where your story grows.”

I didn’t want to fight with my grandmother and tell her how stupid I thought this was. We didn’t talk very much these days. She unfriended me on Facebook for sharing too much of what she called “socialist propaganda.” My mom had graduated from sobriety camp and was now living in her house. We talked on the phone, once every few months and updated each other on our lives. I would set aside an afternoon or two on the rare occasions I went back to California. We still didn’t know each other very well.

Grandma Catherine urged that it might be proactive for us to be aware of any predispositions to health crises. I suspected this might be a way for her to intervene on the severed ties between my mother and I. I spit into a tube to appease her and laughed.

***

Ancestry.com works almost like a dating profile. After you submit and your saliva is processed in a lab, you receive an email. The website generates a DNA story, with ethnicity estimates and an interactive map pointing to where your DNA traces are spread across the globe. There is a page to build out a family tree. (AncestryHealth now can only be accessed with an extra fee.)

Your DNA is then compared to other users’ profiles in the database. Ancestry uses a system they call a “match confidence.” Identical DNA doesn't always immediately indicate relation. The score is based on the amount and location of shared DNA with another Ancestry.com user. DNA is measured in centimorgans. Depending on the number of common centimorgans between you, Ancestry lets you know the likelihood that you share an ancestor with that person. Based on the amount, Ancestry can ponder a guess at the possible relationship. Siblings share 2,400—2,800 centimorgans of DNA. Parents and identical twins share around 3,475. Your 5th cousin will have 6-20 shared centimorgans with you. You can then scroll through any compatible matches and decide if you want to slide into their DMs.

Ancestry DNA results take about 6-8 weeks from the point of dropping your spit box in the mail. Catherine had been meticulously managing our profiles, updating her own tree and crafting one for my mom. When the results came back, we spent a night over the phone saying “oh wow, how interesting” to single digit percentage matches in Portugal and France. We confirmed my mother’s birth father was of Mexican descent, her mother Irish. My dad’s name automatically generated on my tree; his brother’s account popped up as a “likely relative.” I didn’t log into the website again until years later.

In summer of 2018, two years after we mailed off our saliva, my mother’s account received a notification message. My mom had a biological sibling living in Encinitas, just a half-an-hour away from Alpine, in the surrounding areas of San Diego where she had spent her entire life. A few months later, my grandmother texted me that my mother’s account had received another notification. So, my mother and her new brother had two more half-siblings, Robert and Tasha.

After my mom called me with the news, I received a Facebook message request sent from Muncie, Indiana. Tasha ___ wants to send you a message: “Hey, this makes me your aunt. I know this is really overwhelming but I am glad I found you guys.”

What happened over the next few years and what I have been trying to document and write down was a story filled with secret siblings, secret adoptions, shared drug addictions, shared traumas, and a newly sprouted tree of people I was related to, and who now wanted a relationship with me. After Tasha called me for the first time, I spiraled. These revelations in my blood, long lineages of addictions and abandoned children, threw me into turmoil and an identity crisis.

As I started graduate studies at the New School in 2019, I resolved to work it out through my writing. My Master’s thesis would be a compelling, magnificent exploration of inherited trauma, genetics, and identity. It would be a piece of writing that would break a thousand hearts. In the spring of 2020, I took a Master’s Critical and Creative Writing seminar to begin the process. I had grand plans of traveling to meet my new stranger family members, conducting interviews, doing the emotional labor of familial reconciliation and emerging from the semester with a near finished piece of writing that I could perfect and disseminate in my last year of grad school.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic happened. We went into quarantine and we went online, indefinitely. I had the beginnings of a draft with no idea of where to take it. I felt unable to do the work to complete it. I still hope that one day I will write down the whole story of my life before and after the DNA test. In this project, which takes pieces from the beginnings of my thesis work, I am taking a closer look at this product that was the catalyst for my turmoil.

With the boom of the DNA business, stories of nuclear families becoming dissolved flourished. DNA tests bring to light infidelities and lies that would have otherwise gone un-investigated. (Ancestry.com even has a service called Ancestry ProGenealogists. It’s like hiring a DNA private investigator if you hit a brick wall in tracking down your biological relatives. )

This information can unravel lives. Your father isn’t your father. Your mother has a secret family. Your third cousin is actually the Golden State Killer. Like with the DNA health diagnostics, there isn’t much guidance on what to do with your genetic information. The complexities of lived experiences can’t always be organized into a cute little tree graphic.

Why is the culture so obsessed with a false sense of “where we come from?” Should a stranger have access to your information on the sole basis of sharing DNA with you? Why was it designed this way and what will be the long term failures and potential injustices of this design?

***

“we tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

quote: Joan Didion | image: the author's mother, location unknown, date unknownThe kit arrives in a clean, neatly packaged white box with simple green and blue accent details. The ancestry logo is a simple sideways leaf. The front of the box says “DNA Activation Kit.” It includes a tube to spit in and mail back, and instructions for setting up your Ancestry.com account. Medical-looking enough to inspire confidence, but not too medical to be intimidating. (The kits are now sold in different tiers, with health reports coming at higher costs to the basic “Origins + Ethnicity” and “DNA Matches” starter kit.)

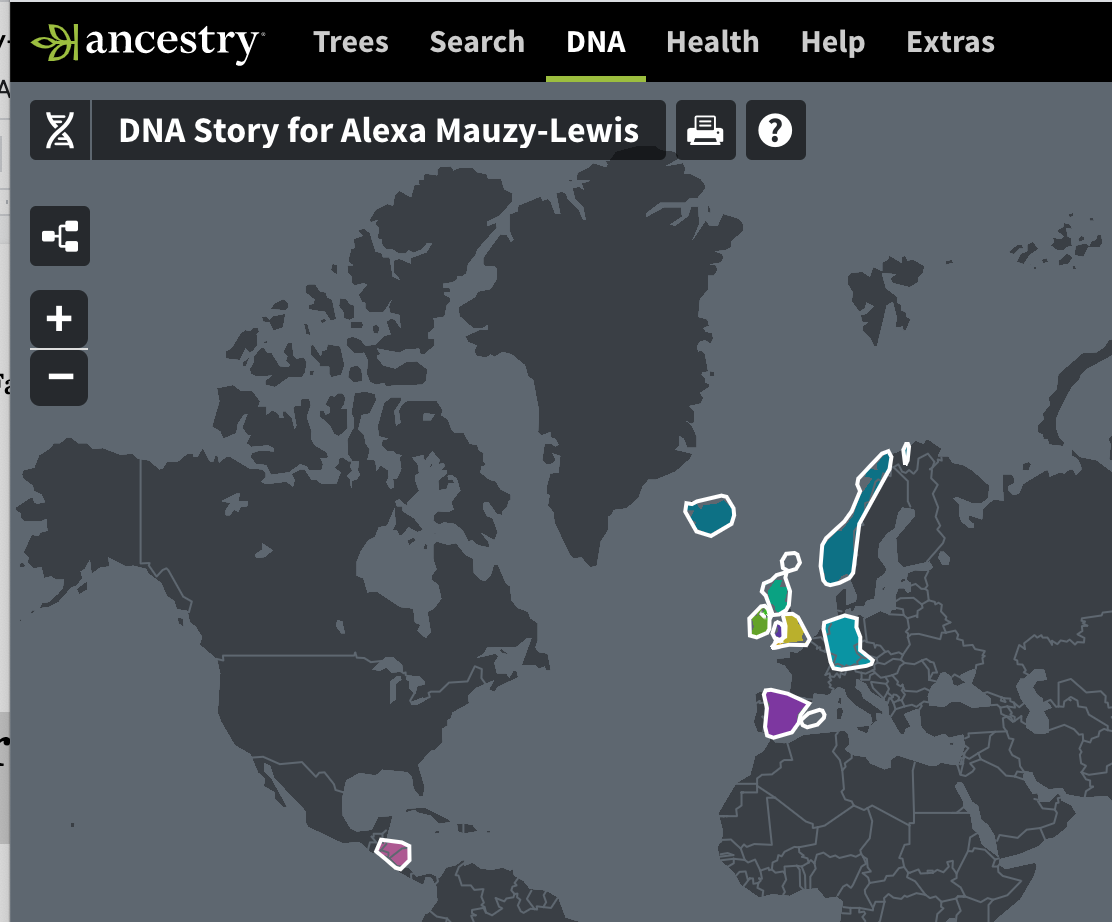

It took me a long time to guess my password to log back into my account on the site. It was connected to a long abandoned yahoo email address. Looking back at my profile now, I can look at a tab called “DNA” with a drop down box to view my “DNA Results Story” and “Ethnicity Estimate.” My DNA story is a colorful map, areas highlighted where my DNA came from. If you click on an area it shares stories of the region’s history, contextualizing your genetics.

By chance, I met someone who worked as “a Context Curator” in the Editorial Department of Ancestry.com in 2012. They spoke to me about their work. I will keep their name anonymous.

“When I started out, there was a lot of experimenting going on. I worked on whatever was asked of me,” they told me. “The first thing I worked on was a massive timeline of ‘on-this-day historical’ factoids. It was boring,” they said. “One for each day of the year. Once that was done, I worked on sample copy for a premium product where users could learn which celebrities they were related to. I remember drafting copy for Benjamin Franklin and Britney Spears. Not sure what came of that—if it was handed off to another team or if it was nixed. I imagined users would like that.”

“The main product I worked on was ‘Historical Insights.’ I think it’s still live,” they said. “The pitch was that it helped people understand the lives of their ancestors. Basically, the idea was we used records: immigration, birth, death, military, census, marriage, etc. to understand where people lived during important historical events. For example, say someone’s ancestor was living in Alabama in 1862. We would suggest they add a Historical Insight to their family tree that detailed the experience of living in the South during the Civil War. The product consisted of a short paragraph and a few images to give ‘the everyday man a sense of what his ancestor’s life was like.’ The phrase ‘everyday man’ was thrown around a lot. I don’t remember receiving more detailed info on the target audience, but I understood it mostly to be white retirees. Over the course of three years, I must have written hundreds of Historical Insights.”

“There were really uncomfortable moments working on some stories,” they described to me. “How do I describe the experience of slavery in 50-75 words? How do I describe a massacre of Indigenous people? A pandemic? The Dust Bowl? The list went on and on. And keep in mind, you’re describing these events for presumed descendants of people who lived through these events. It had to be handled with care and thoughtful research. While I think that there was value in sharing short blurbs about American history with users who probably don’t know about it, for deeply serious topics, there needs to be context to do it justice. And there wasn’t space for a context in this product.”

When I asked them about concerns around the use of DNA data, they said, “The whole thing seems wrong to me, which is why I chose to not use the product, despite my coworkers saying how exciting it was. They added, “ I should mention my mom did, so I guess I’m in the system anyway. The most exciting thing she learned is that her ancient ancestors may have been French. She is convinced of that, but I’m not so sure. Also, who cares?”

***

Ancestry.com tells me I have 636 4th cousins or closer in their system. I clicked on the “Trees” tab. There was my dad, my mom, and me. You have the option to add building blocks to your tree. I tried to build a more accurate tree for myself. It was nearly impossible. Adding in things like divorces, half siblings, stepparents was really complicated. I couldn't draw a line between myself and the people who actually raised me.

Because culture is not genetic. In 2018, the group Anthropology blog, anthro{dendum}, published a post titled “About those Ancestry dot com commercials” They describe an Ancestry advertisement that features a man named Kyle. Kyle begins the video stating, “Growing up we were German.” anthro{dendum} writes, “He danced in a German dance group, wore lederhosen, and so on. Culturally, his family was ‘German.’ ” But then Kyle takes an Ancestry DNA test and learns he has zero German ancestors, and his DNA actually came from Scotland and Ireland. “Tracing your family genealogy can be fascinating,” anthro{dendum} elaborates. “That’s not the problem here. Kyle’s case is a perfect example of how misguided these tests can be. From an anthropological perspective, one of the primary issues is that these tests seriously conflate culture and biology. The second issue is that these tests paint an oversimplified, if not outright false picture of culture, history, genetics, and genealogy. There is no “Irish” or “German” gene or combination of genes. That’s just not how it works. Culture is shared, patterned, learned behavior.”

Ancestry’s marketing strategy to emphasize its ability to reveal proud cultural lineages and make “broken” families whole, paired with the presentation of results in the form of a map reifying a notion of genetic identity as geography, warps our ontologies of self. As anthro{dendum} writes, "The take home message is basically that these DNA tests tell you who you really are, despite your actual upbringing, cultural practices, family histories, and memories.”

*** explore ancestry commericals ***

Ancestry Commerical | Kyle

Ancestry Commerical | Sufragettes

Ancestry Commerical | Descendants of Honor

Ancestry Commerical | Queen Latifah

Kim Tallbear, an indigenous scholar based at the University of Alberta and author of Native American DNA, further writes, in response to an Ancestry.com ad featuring a woman “discovering” her Native American heritage, "We construct belonging and citizenship in ways that do not consider these genetic ancestry tests. So it's not just a matter of what you claim, but it's a matter of who claims you."

As I tried to expand my tree to add in my two half sisters, who I have lived with my entire childhood, I realized that the building blocks only give two gender options and an "unknown" option that it defaults to if you don't pick, which results in this gray amorphous person icon. (That is whole another wormhole to unpack.) Ancestry also can pull up public records related to your DNA matches and show you them, like a yearbook photo of my mother that popped up on my account. If someone matches DNA with you, you have the ability to contact them through the website, which leads to even more complications. What do you owe someone just because you share DNA with them?

Beyond this interpersonal conflict, there are a lot of serious cultural consequences of this database. Dr Sheldon Krimsky, Professor of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University, gave a presentation on “Ancestry DNA Testing and Privacy” to American Medical Writers Association members at the New England Chapter meeting on September 24, 2018. Documented by Haifa Kassis, MD and Deborah A. Ferguson, PhD for AMWA Journal, they write, “It may not be clear to consumers that the contracts they sign to have their DNA sequenced for ancestry testing often include clauses that give away their rights to profits from any future products developed by using their genetic information.” They further elaborate that, “DNA sequencing data collected for ancestry analysis may also be requested by law enforcement agencies. Unless there is a court order, it is up to each company to decide whether it wishes to cooperate with law enforcement.”

These are concerning tools to be at the disposal of the police, or any company that buys out the data. The promises of DNA testing fall short, and the future ramifications can cause distress when you think about them for too long.

***

Conclusion

I think about my phone call with Tasha, often. In the weeks after those first time we spoke, she sent me facebook messages almost daily, ringing around in the void of my silence:

“Hi honey hope you are doing good.im up early my parole officer just came.anyway yr mom hasn't contacted me im worried she won't.i don't want u to say anything im just sad.I know it's hard on her.keep trying to tell myself that. Hows work? I still can't believe all this I have a niece and a sister I never have had how sweet .love u”

“Hi Alexa...hope u are doing good I have so much going on a little depressed but I will get over it.just wanted to say hi and I love u.my only niece.awe...never heard from yr mom I made all these plans to be her best friend oh well.you are beautiful my daughter is coming over for the weekend.i will have someone to hold lol.ttys”

“💖💖💖”

“Keep yr head up beautiful”

“Very much just going through some things ok I'm sorry”

I was torn between empathy and caution. She was reaching out to me for something. I didn’t know what it was. I felt paralyzed when I thought of responding. I didn’t want to be cruel. I also didn’t want to open myself up to her chaos when my family structure was complicated enough as is. Was I obligated to have a relationship with these people because of our shared centigram count? I hardly trusted my mother. Her genes didn’t raise me, but I still carried them.

When I first sat down to write about all of this, I called my Dad. I was beginning to not trust my own memories, and I needed grounding. My father and I never talked much about my mom. I had always thought of him of a man of few words, not someone prone to talking about his own emotions. I realized that I also never asked him to.

“Dad, was she sick when you met her?”

He shared details I had never heard before. How they met, what she was like when they were together. Their relationship was always very abstract to me. My birth was almost immaculate in my head. I was not born out of any love or passion. I just came into existence between these two people who hated each other. I had never known them together.

My dad asked if I was writing about DNA because I was afraid I would inherit certain things from my mother. I told him I didn’t think so. I just wanted to make sense of it all. But how could I when I hadn’t even made sense of my relationship to her.

“You must have gotten more of my genes,” he said. “You and I are more pragmatic” I laughed at him. He told me he was proud of our family, that my sisters and I stayed so close. “My brothers can’t separate me from our parents, and what they did to us. And I have all these half-nieces and nephews I’ll never know.”

“Maybe you should take a DNA test too, Dad.”

He guffawed at me. “No Lex, I am not giving Uncle Sam my DNA.”

I didn’t mention that, to some extent, he already had via his daughter’s saliva. I could hear my little sister in the background, asking our father to keep it down because she was watching Friends. My heart ached with how much I loved her.

I was still feeling hopeless about my work. While these services draw people in with elaborate maps, trees, and insistence that you need to know your genetic makeup to know yourself, this information can be abused and misinterpreted in countless ways. I felt like I knew even less about myself. I never even wanted to take this test in the first place.

After we said goodbye on the phone, my dad texted me a few moments later. “The more I think about it the more interesting what you’re writing becomes. I think it would strike a chord with a lot of people.”

We look to other humans as anchors, grounding in the chaos. We tie ourselves to each other to establish a sense of place. These connections are created at random.

Whether or not to keep them, is our own choice.

After that, I opened up Facebook.

“Hi, Tasha. I am sorry for not reaching back out sooner. Would you want to talk and catch up soon? Love, Alexa.”

*** TO BE CONTINUED ***

BIBLIO GRAPHY & SUGGESTED FURTHER READINGS

TallBear, Kim. Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science. University of Minnesota Press, 2013. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt46npt0. Accessed 11 Dec. 2020.

Kassis, Haifa, and Deborah A. Ferguson. “Ancestry DNA Testing and Privacy.” AMWA Journal: American Medical Writers Association Journal, vol. 34, no. 2, Summer 2019, pp. 62–65.

Scudder, Nathan, et al. “A Law Enforcement Intelligence Framework for Use in Predictive DNA Phenotyping.” Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences, vol. 51, Feb. 2019, pp. S255–S258.

Leetz, Kenneth L. “An Unanticipated Outcome of a DNA Ancestry Test.” American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 175, no. 12, Dec. 2018, pp. 1167–1168.

Wallace, Helen. “Ancestry DNA Testing: Who Could Track You and Your Relatives?: When You Send Your DNA to an Ancestry Testing Company, They Might Not Be the Only Ones Looking at It.” GeneWatch, vol. 31, no. 1, Jan. 2018, pp. 9–10.

“Trauma in Childhood Associated with Risk to Female Offspring.” Brown University Child & Adolescent Psychopharmacology Update, vol. 20, no. 1, Jan. 2018, pp. 1–6. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1002/cpu.30267.

How a DNA Testing Kit Revealed a Family Secret Hidden for 54 Years, Time, Dani Shapiro

Your DNA is a valuable asset, so why give it to ancestry websites for free?, The Guardian, Laura Spinney, 2.16, 2020

Do a DNA test to 'find out my roots'? That's complicated for a black woman like me, The Guardian, Derecka Purnell, 2.7.20

How a Genealogy Website Led to the Alleged Golden State Killer, The Atlantic, Sara Zhang, 4.27.2018

Found: genes that sway the course of the coronavirus, Science Magazine, Jocelyn Kaiser, 10.13.20

“About those Ancestry dot com commercials”, anthro{dendum}, 5.25.2018